Rama Duwaji on Western beauty standards and 'Razor Burn'

Originally published July 27, 2018 on Bigmouth Comix.

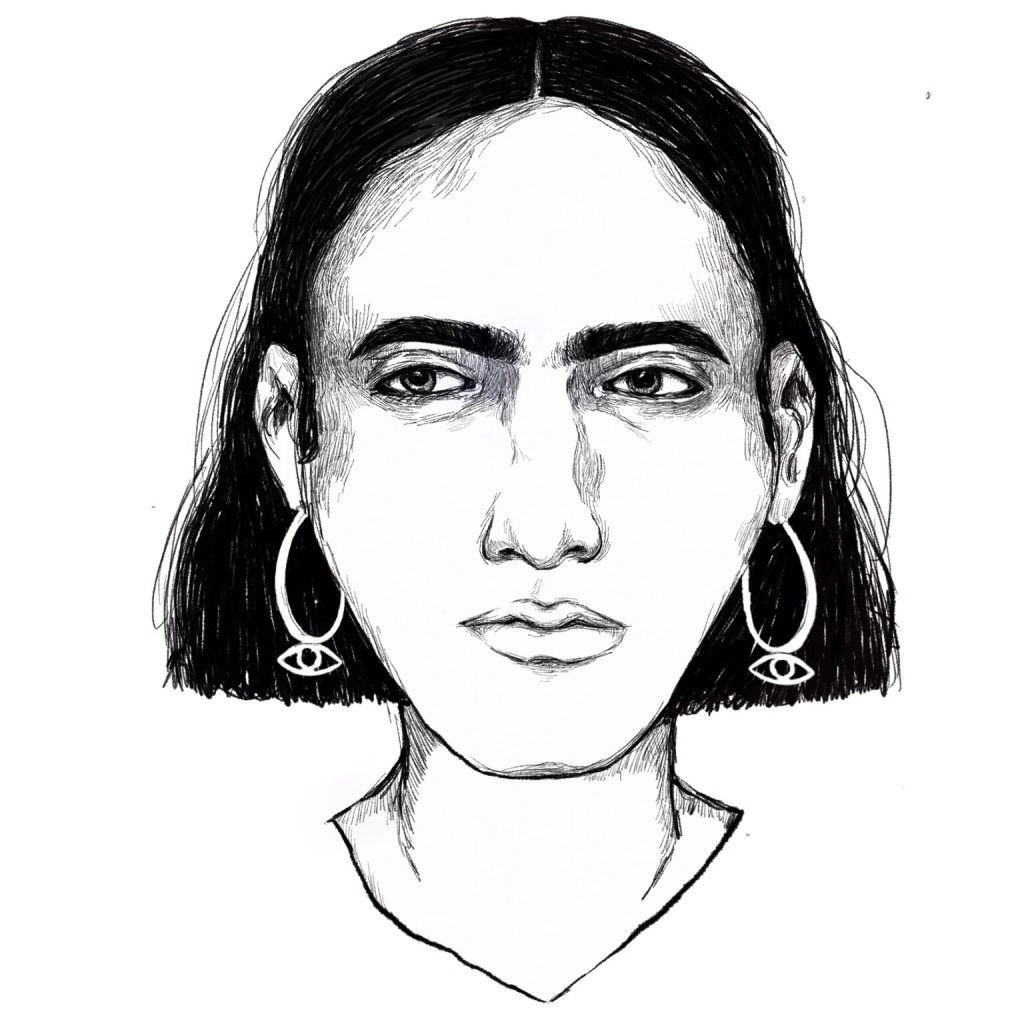

Rama Duwaji is a Syrian illustrator and comic artist. She is currently studying at Virginian Commonwealth University's School of the Arts. Rama's work often works to challenge Western beauty standards. Maamoul co-founder Leila Abdelrazaq talked to Rama about her process and motivations, as well as her short comic, Razor Burn.

Leila Abdelrazaq: Could you introduce yourself and tell us a little bit about you?

Rama Duwaji: I am a 21 year old illustrator from Syria, based and studying Visual Communication (a mix of illustration and design) in the US.

LA: When and how did you begin illustrating?

RD: I was making art since high school, mostly out of boredom in classes, and I’ve had sketchbooks since I was in 6th grade (they were the worst, but still part of the process,) but I only decided to pursue art/illustration as a career last minute in my last few months of high school while applying for university. I’m glad 17-year-old me decided to take the jump, because I honestly can’t see myself doing anything else. I think I started taking my art seriously during my first year in college, setting actual goals for myself, exploring topics within art and working on my social media presence.

LA: Your work often deals with themes of western beauty standards. How do you confront this in your work?

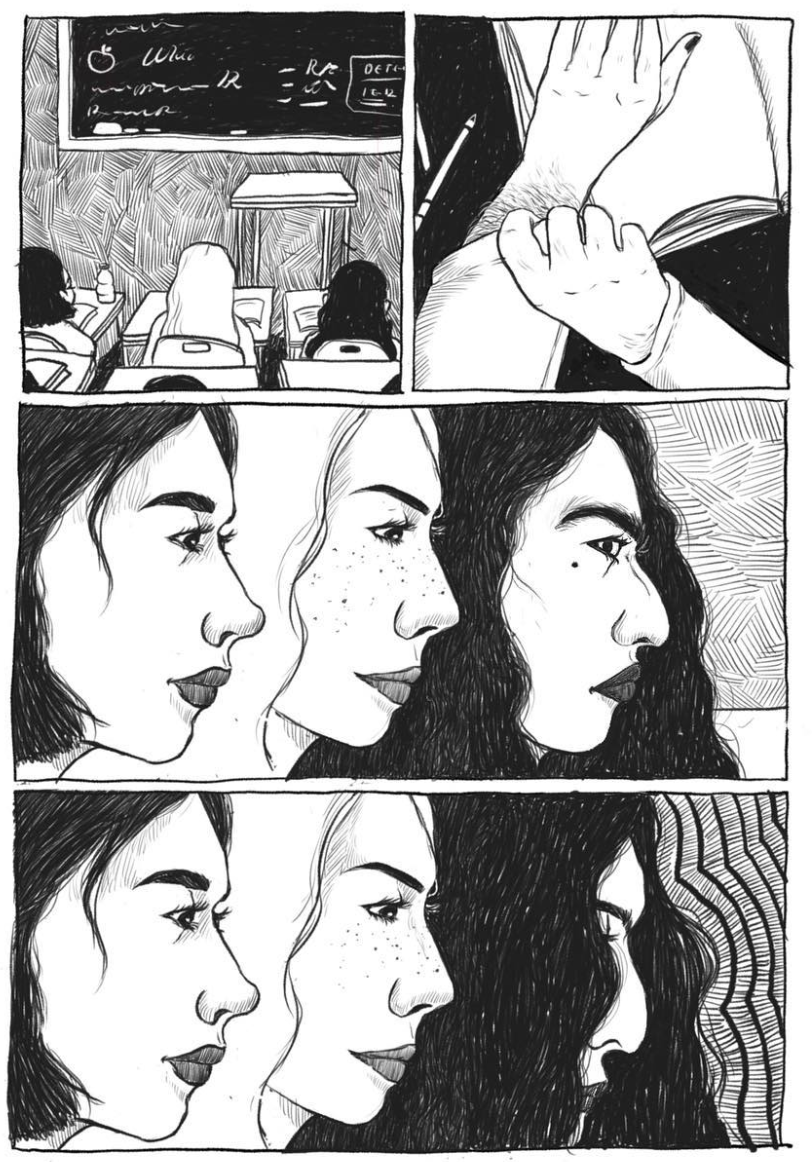

RD: I’ve always enjoyed drawing portraits. I think its really representation thats important, by integrating more diverse beauty in the art world, the standards change and move away from the western beauty ideal. I only really felt that I was starting to do this when I made Razor Burn, and got an overwhelming response to it.

LA: Can you tell us a little bit more about Razor Burn? How did the idea for this story come about? Why was working on it important to you?

RD: So my first little graphic novel ever, Razor Burn, was actually birthed in a semester long project in an art class about mental health, physical health, and societal issues. I decided to make an accessible graphic novel for young teens of color about the pressure of Western beauty standards, and the prevalence of mental health issues such as body dysmorphia, anxiety, and depression. The comic was based off the experiences of myself and many friends/family around me. It is a silent novel with no words, just images, (hopefully) making the book more accessible for people of different languages, socioeconomic, and education levels. It sounds cliche, but through the protagonist’s struggles with her body/facial hair, foreign features, and her experiences in a white majority school, I wanted anyone reading it, who might’ve felt bizarre and alone struggling with body image or mental health, to realize that hundreds and thousands of women have gone through the exact thing and came out thriving and confident despite it. When I started sharing some of the illustrations online, I had so many people approaching me, telling me that they had experienced the same thing, which emphasized to me that taboo issues in the MENA region such as mental health needed to be talked about.

LA: Most of your work is black and white, but you’ve started using some color. What is your relationship to color in your work? Why and when do you choose to use or not use it?

RD: I think I started using pen because it was just always the most accessible tool for me, since I was in high school. From then on, it just felt natural, I felt no need to add color to my work, and it felt forced when I tried. I recently started experimenting a little with color here and there, just to practice the skill and to shake things up a little. It helped me get out of an art block when I was feeling drained after big project that was solely in black and white. I also use select colors when making art aimed for children/young teens in the form of both book illustrations as well as murals, which is something that I found I enjoy.

LA: Can you share some of your creative inspirations? Whose work do you admire recently?

RD: Right now my creative inspirations are cave formations, after I visited some amazing caves in Beirut and fell in love with the endless lines and shapes the rocks make. As for actual people whose art I admire, they’re endless. Some top favorites at the moment are Carson Ellis, Rithika Merchant, Betsy Walton, Ronan Bouroullec, Rachel Levit Ruiz, and always, Lucian Freud.

LA: What tips do you have for aspiring artists and illustrators?

I don’t feel like I really have enough authority to give people tips yet, since I’m still kind of in the process of figuring out what works for me as an artist. But if I was to give someone advice it is: don’t box yourself into one style and medium or art form all too soon. I do enjoy painting and working with multi media and textures, but I don’t make much of it because I think I’m just better at ink drawings? Its also more accessible and more “likeable” for my Instagram audience, which definitely should not have been my focus, but its easy to fall into that validation trap. I’m just now in the process of working to find that sweet spot between my love for illustration and for some of the more fine art aspects that I enjoy. I also enjoy digital art and its flexibility, and that's ok, different mediums work for different things, and I think that mutifacetedness (is that a word?) in art is something to embrace and use to your advantage.

You can support Rama’s work by following her on Instagram @ramaduwaji, checking out her website, and buying prints of her work at her Redbubble shop.

Love Letters to Iran: An Interview with Beeta Baghoolizadeh

Originally pubished February 16, 2018 on Bigmouth Comix.

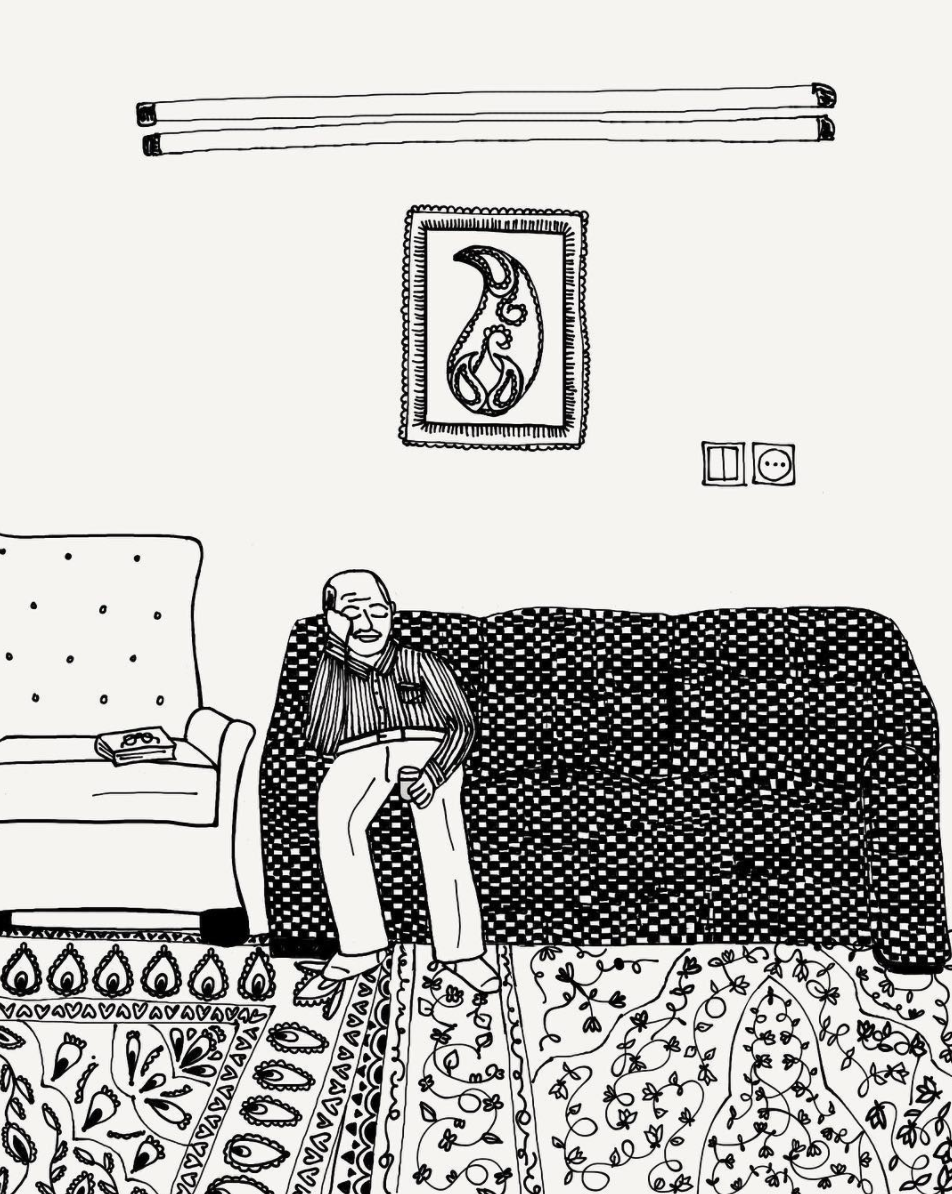

Beeta Baghoolizadeh is an Iranian illustrator, historian, and editor based out of Philadelphia. Her project, Diaspora Letters, is a visual tribute to a rapidly changing Iran. Using black and white illustrations and animations that are with texture and detail, the project is a historian-artist’s attempt to capture fragments of her homeland in the current time and place. Using drawings of primary sources like letters and photographs, as well as illustrations from daily home life and mundane family scenes, Baghoolizadeh’s work captures a piece of Iran’s ever-changing present, while acknowledging the persistent influence of the past. That the entire project, slated to become both a film and a graphic novel, is drawn within the context of diaspora, adds to the way that past and present run concurrently in her work, creating almost an archive of particular places, feelings, and people that cannot be captured through photographs or other primary sources alone. We interviewed Baghoolizadeh to find out more about her approach to her work, and how her multiple disciplines converge and influence each other in Diaspora Letters.

Leila Abdelrazaq: When did you begin creating art and illustrating? What drew you to this medium as a form of expression?

Beeta Baghoolizadeh: Well, I'm a historian of modern Iran, so I've traveled to Iran pretty regularly in the past few years to conduct research and visit my relatives. And this last time I was in Iran—August 2017—I was overwhelmed by how quickly everything in Iran changes. I had to reorient myself with new geographies and landscapes—streets, neighborhoods, etc. The rapid growth of the urban sprawl is a lot to take in.

So I started drawing. I started with my grandparents—I drew them, their house, just mundane scenes of the everyday. I felt that if everything is in a constant state of flux, I would need personal markers for preserving my memories, because it wouldn't be the same the next visit. But my drawings have developed in different directions, some more autobiographical, some more distinctly rooted in a broader history beyond my own family.

As a historian, I'm interested in how the past gets translated into the present. And visual media gets read and understood in such a different way than anything textual—so my arrival at this medium has helped me move beyond the limits of historical discourse.

LA: Tell us about how your drawings have developed since then. Where are you taking these drawings?

BB: In August, I started posting some of my illustrations on Instagram, where I've been able to share small anecdotes and relevant histories for the different illustrations. Most of these drawings will somehow be incorporated in one of two projects I'm working on concurrently.

The first project is a documentary film that I'm putting together with animator/filmmaker, Shane Nassiri. As it stands, the documentary will string together stories of families living in Iran and in diaspora in the 20th century, and how they remained connected through post. Mail—as you probably guessed from the name "Diaspora Letters"—has been an important theme for me. What kinds of things were being sent back and forth? Why? And what do they tell us about the political, social, and cultural environment? Those are the kinds of questions that we want to get at in this project.

The second project is a graphic history. I'm excited to be working on this book, which follows a family story and unravels some common preconceptions about urban family life in the past century. Iranians witnessed a lot of changes in daily life during the twentieth century, and I love the idea of exploring that visually, since words can only express so much.

LA: You’re also a historian and an editor at Ajam Media Collective. How are these practices linked for you, and how do they impact your approach to your creative work?

BB: Diaspora Letters grew organically out of my work as a historian and an Ajam editor. Part of being an editor at Ajam is making sure that people who are not necessarily academics have access to all sorts of amazing research on the Persianate world. A few years ago, I set up the Ajam Archive—a crowd-sourced digital archive of twentieth-century life in the Persianate world. It has been really exciting developing it, seeing what people are comfortable with sharing and what kinds of stories are behind the photographs, newspaper clippings, and clothes. Not only am I learning about the histories behind particular items, but I'm also learning about what people feel they can and can't share from their family collections.

Those sorts of absences are, for historians, really interesting. And that's what I think this illustrative medium offers in terms of histories—it can show what didn't get photographed, or what people didn't want to photograph, or what people photographed and don't want to show on a public platform. There's a lot missing in these conversations, and drawing them fills the gap to some extent. Of course, the drawings themselves just as selective as the photographs—I can’t show everything that’s missing! But theoretically, the drawings can show anything, and that excites me.

All of these experiences inform my graphic work. I want people to access and navigate their own relationship, visually, with the material. It evokes a different series of emotions than an article, and I wanted to be able to tap into that.

LA: You often work from photographs, letters, and other artifacts. How do you select these objects and what is the importance of integrating them into your illustrations?

BB: I love working with tangible objects and abstracting them in my drawings - this practice is definitely influenced by my academic training. In some ways, I'm trying to stretch how far textual analysis of primary sources can get us - instead of realistically replicating the written word in my work, for example, I deconstruct them into scribbles, forcing the viewer to rely on the entirety of the illustration to determine the context. It's very different than how we use sources in history, and I appreciate the flexibility illustration affords me in pushing these boundaries.

I work from photographs, but a lot of the illustrations don't necessarily end up looking like the people in the original photographs. In some ways, I'm trying to anonymize and vernacularize the images. So I'll change the shape of the eyes, nose, lips, etc - an urge very different from the kind of typical academic work that requires attention to accuracy and faithfulness to the sources we use.

Sometimes it works, and the result is different people telling me that the person looks like their aunt or some other relative. Other times, my mom will look at a drawing and say, "Wait, that's me! That's my hair!" I love both types of reactions and make note of them as they happen.

Outside of the Diaspora Letters exhibition at 12Gates Arts in Philadelphia, PA. Photograph by Sahar Irshad.

Baghoolizadeh with some of her illustrations and animations, on display at 12Gates Arts in Philadelphia, PA. Photo by Sahar Irshad.

LA: Since you’re creating these illustrations in the context of a book and film, how was the process of using those images to put together your solo exhibit at 12Gates Arts? Did it change the way you’re thinking about the process of creating the book?

BB: Working with 12Gates and sharing my digital drawings as individual, stand-alone pieces has been a very generative process for me. The 12Gates exhibit mostly focused on scenes of everyday life - the banal, the mundane, the sort of things that are too boring to be circulated in the media or preserved in institutional archives. Even though a lot of the pieces I showed at 12Gates fit into a larger narrative arc, showing them in no particular order with no linearity allowed me to explore the theme of fragmentation. Everything we can know about Iran is ultimately fragmented, not only because of the diasporic distance, but also because of how quickly everything is changing. It’s good to remember this that when writing stories—real life changes in unexpected ways, leaving behind the past more rapidly than we sometimes expect.

LA: You often reference your family’s reactions to your drawings in your instagram posts. It seems the process of creating this work is one that involves your entire family in a very intimate way. What do you think is the significance of creating work in this way?

BB: I love my family and I love incorporating them into my work as both subjects and consumers. They have a great sense of humor, and when I can refer back to a quip from my grandpa or someone else, it lightens the heavy emotional content underlying the process.

In many ways, my drawings are all kind of love letters to not only to Iran, but also to my family all over the world, the majority of whom still live in the homeland. Even though I'm fluent in Persian, there are conceptual barriers that language can't overcome, so the visuals help.

You can follow Beeta's work at @diasporaletters on Instagram and Twitter, or follow her personal Twitter account @beetasays. And if you would like to be in touch with Beeta, shoot her an email at beeta@diasporaletters.com.

Riso for all: A new women-run community press in an East London library

Originally published April 4, 2017 on Bigmouth Comix.

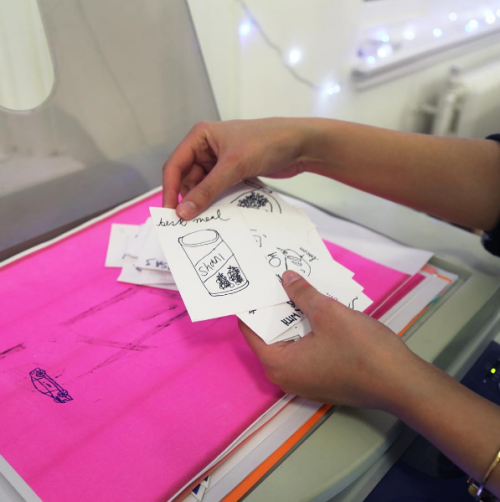

Rabbits Road Press is a community risograph print studio and publishing press run by OOMK (One Of My Kind) in Rabbits Road Institute (Old Manor Park Library). The small-scale publishing press provides printing and book binding services for artists and local community groups in Newham.

A responsive programme of workshops, drop-ins and events over the next six months will explore a contemporary model for community publishing, bringing together artists, designers, writers and local people. The project builds on Rabbits Road Institute’s initiative to establish an accessible and diverse community art space to support the development of new skills, knowledge sharing and social exchange for people living in Newham.

Bigmouth spoke with one of the founders of OOMK and Rabbits Road, Sofia Niazi, to learn more about their motivation and plans for the press

BM: How did the idea for Rabbits Road Press come about? Who is behind it? RR: We wanted to get a risograph machine for ages. A few of our friends have riso machines so it didn’t seem like such a crazy or unachievable idea to get one of our own and start using it to print our own artwork and zines. I illustrated and riso printed Intifada Milk, written by Arwa Aburawa, in teal and brown and have been a bit obsessed with the process ever since, it gives such a nice effect and is so much easier and more immediate than a more manual ink layering technique like silk screen printing. Rose interned at Hato Press for a bit too so it was something she was familiar with too but in a more advanced and technical way.

The idea for Rabbits Road Press came about when we were between studios last year. We moved out of our previous studio, which was in North London, because the rent was too high so when Create London approached us with a space in Old Manor Park Library and asked us to propose a project which we were only too happy to. A lot of our practice (with both OOMK and in our personal work) is to do with publishing, community engagement and education. We came up with Rabbits Road Press, a community risograph print studio which was open to the public and would provide free training and workshops. We thought a good way of creating a community art space would be to entice people in with free riso printing inductions and workshops and keep them coming back on Open Access Tuesdays with low printing prices and a free studio space.

BM: Tell us a little more about One of My Kind (OOMK). How/why did it come together, and what drove your work initially? RR: OOMK is a biannual zine about women, art, activism and faith. The zine is currently run by myself, Rose and Heiba, but there are about 15 women in OOMK collective who we regularly collaborate with and host events with. We also host DIY Cultures which is an annual day festival about zines, art and activism. We were initially driven by the desire to create a space where women, particularly Muslim women, could share their art and ideas and discuss issues that were important to us, issues that often had no resemblance to the type of ‘discussions’ that were taking place in mainstream media.

BM: What do you hope to achieve with Rabbit’s Road Press? What are your goals? RR: We hope to make art-making and the arts in general more accessible. We want to create an environment where people can feel comfortable to explore their ideas and creativity and to take control of all means of production. For a lot of people, pursuing an art school education is increasingly difficult due to high tuition fees so with Rabbits Road Press we’re hoping to create a less formal and more accessible alternative.

BM: How can people get involved or support? RR: The doors to Rabbits Road Press are open to the public every Tuesday 2-7pm so come and get a free induction and start making your own work! We’ve have interest from community and activist groups with very low/no budgets to print ephemera so we’re looking to set up a fund for that but we’ll get more info on our website in the next few weeks about how people can donate and use that.

BM: Anything else you want us to know? RR: We’ve got some zine fairs coming up! We’re hosting Zine World, 4 March at Rabbits Road Press, details for booking a stall will be on our website very soon. This Monday we also announced DIY Cultures 2017, the day festival will take place at Rich Mix in East London again and will be on 14 May, to book a stall go here, international zine makers very welcome to apply!

For more info, visit Rabbits Road’s website. Also follow them on twitter andInstagram for more of their work!

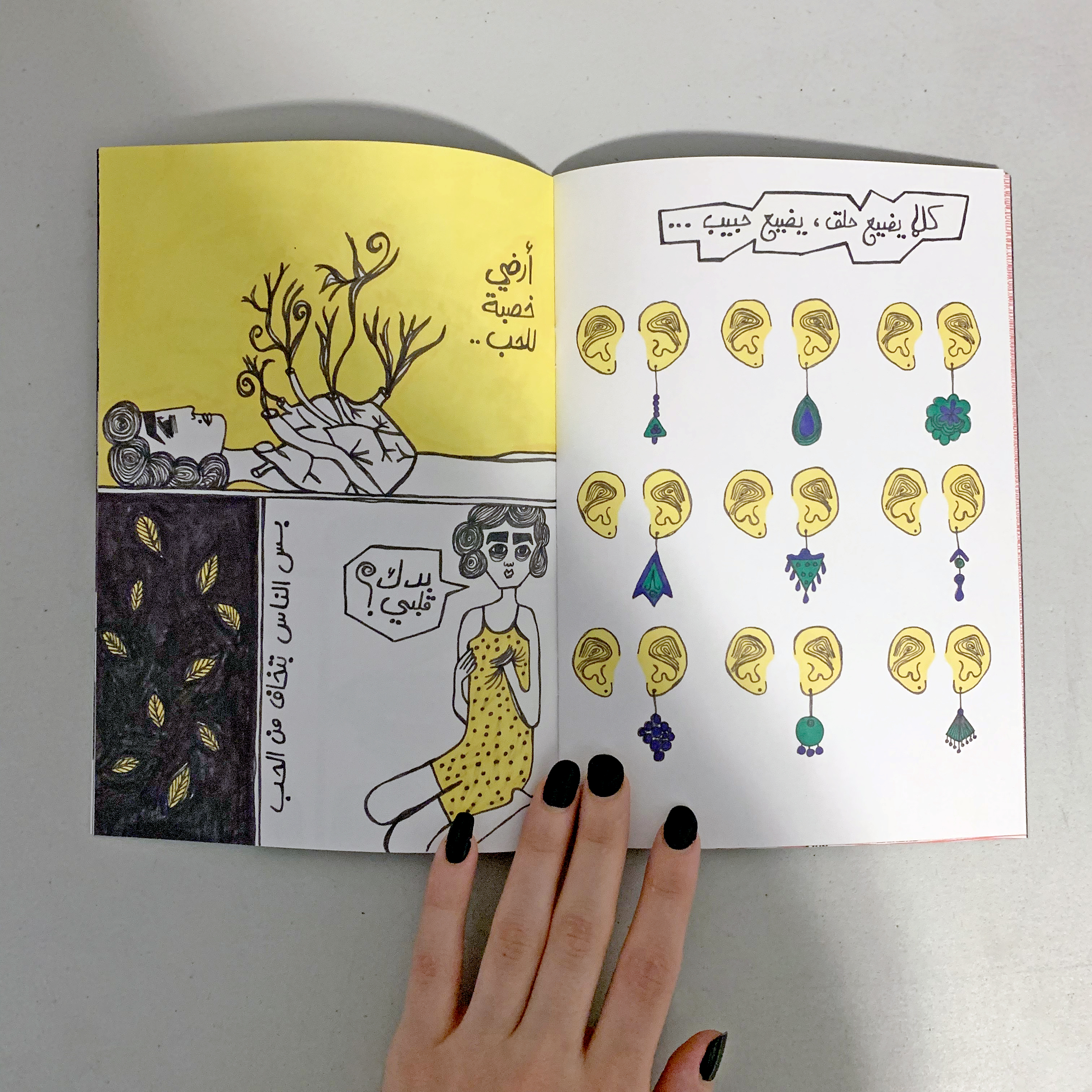

Not from Mars: Rawand Issa’s new zine is a powerful manifesto on life, love, and being a girl

Originally published April 4, 2017 on Bigmouth Comix.

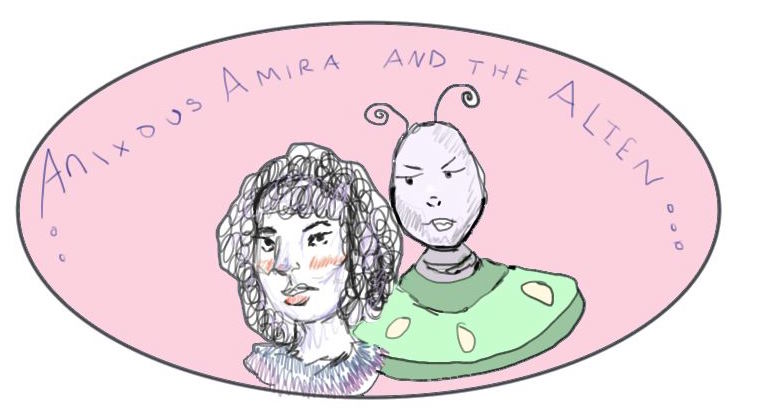

BIGMOUTH is so excited to welcome Lebanese illustrator Rawand Issa to the family! (We formerly featured her work on Bigmouth here.) Her fanzine, “Not From Mars,” is a personal comic manifesto of sorts on life, love, and being a woman. Hers is the first zine from Lebanon that we have printed in the U.S. and will be distroing through Bigmouth!

To learn more about Rawand and her work, we interviewed her. Read on for more!

BM: Tell us about yourself as an artist. How did you get into making comics?

RI: I’m not sure if I can call myself a comic artist, yet. Since I’m new to comic making. But I know I am an illustrator. I actually worked as a writer for 5 years in the local journalistic field, before switching into Illustration “professionally” in 2015. Illustration, even a bit of painting (on canvas) was a hobby I used to enjoy. I was more passionate about journalism and documentation. Until I was introduced to Joe Sacco and the term Comic Journalism! I decided this is what I’m going to do. I’m going to be a comic journalist!

BM: What caused you to create ‘Not From Mars’? RI: The most books that influenced me are autobiographies. For example, Nawal ElSaadawi’s “مذكراتي في سجن النساء” actually encouraged me to take actions in my life. It’s powerful to tell people that this happened to me! Rather than, this happened. The concept of Zines is new to me, and I was amazed by the fact the one can produce a publication by their own, without having to go through the process of publishing houses and the market. It’s a revolutionary act! “Not from Mars” talks about situations that a girl (which is myself) living in a conservative, capitalist society. The situations are common to many of us insofar as the personal is always in one way or another also political and thus public.

BM: What other comics or illustrations have you created that you are proud of?

RI: I worked on some cartoons that was published at The Legal Agenda Magazine, about the conditions of Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Those means to me the most for the responsibility I felt while working on them.

BM: Any new or upcoming works that we should look out for? RI: Yes! We’re starting a comic zine collective called ZEEZ! 5 young comic artists and myself - based in Beirut, are starting a collective to produce zines seasonally. We’re hoping to launch our first work in June!

You can buy a copy of Not From Mars in the shop. And follow Rawand on instagram @rawandissa_ for more of her work and updates on ZEEZ!

Cyborgs and the Somali Diaspora: A Converstaion with Gothlime/Halima Salah

Originally published June 1, 2017 on Bigmouth Comix.

Halima Salah is a Somali-Canadian artist and civil engineer. Raised around the world, Salah has been living in the UAE for the past nine years. Her zine-making and illustration work explore themes of technology, alienation, and the absurdity of the modern human condition. Her work and zines are visually striking, making use of jarring, bright neons and pastels, merging illustration, glitch art, and digital collage. We interviewed Halima to learn more about her art, process, and the projects she's currently working on.

Leila Abdelrazaq: Let's start at the beginning. How did you first get into in zine-making and illustration?

Halima Salah: I’ve always been doodling but I only recently got into zine making, influenced by the incredible people who make their own zines I decided to try it out. I fell in love with it. I found so much inspiration online by reading zines that I would find out via twitter (Jaffat El Aqlam, Somali Semantics etc)

I also love reading scanned old goth zines via Flickr.

LA: Tell us about the idea behind your zine .BYTE and why you began working on it.

HS: .BYTE was born during last year’s final exam season at a library in Sharjah. After one of my most stressful exams, I had a brainstorming session of concepts. I was always interested in zines and creating a space to express certain interests. .BYTE is linked to the concepts of how aliens would probably read us. The zine is a guidebook and collection of different pieces for them to understand us. .BYTE is a zine for both aliens and humans who want to bite back at the world when they can’t understand it. I co-curate it with Eman AlEghfeli, we’ve known each other since high school. Eman and I also shared similar interest in specific colors and music.

LA: Cyberspace, technology, glitch art, and the internet are clearly a big part of your work, could you talk about why? HS: Cyberspace and technology are huge part of our lives. I grew up with the internet (like many people) but I used it as a form of escapism, which can be healthy and unhealthy. I’ve always loved art that created it’s own world since I found the real world chaotic and ugly. I always loved making my own form of reality by reading and writing a lot of fanfiction and roleplaying. I start to notice that whatever I absorbed online and through the TV did bleed into my art, from fanfiction.net to Spacetoon that would watch in Somalia.

LA: .BYTE is a partially digital zine. Do you do print copies of the zine? Why or why not, and what to you are the merits and drawbacks of digital zines versus printed ones?

HS: .BYTE is URL and IRL. Eman and I have not started selling the zine but only have limited copies printed for exhibitions. The print versions will start to become available later on this year. I usually find that digital zines are more accessible, I benefited a lot from digital zines. Living in the UAE meant access to a lot of the zines would be a little bit more harder. I only recently found more Middle East based zine making folks.

In our first digital issue of .BYTE we had embedded music, which would be impossible if it was in print. I would say the only downside of print is the lack of flexibility of some pieces that might be in mp3, gif etc.

LA: Why the theme of Alienation for the first issue? Is this a common theme throughout your personal work? HS: I’ve always felt alienated and found solace in cyberspace for expression. This world is chaotic and I just look at it in a way-how tragic we really are. I would see human beings as parasites on this planet constantly taking but never giving back fully to nature. I know it’s a bit too pessimistic but I do have hope for humanity. Alienation is a theme in a lot of my work because I love science fiction and I’ve always felt like an alien or a glitch in the system. I feel like I am an alien-a foreigner, an immigrant...and constantly navigating in those spaces. I’m pretty sure actual aliens are laughing at our condition. I always like to imagine how they’d look at us.

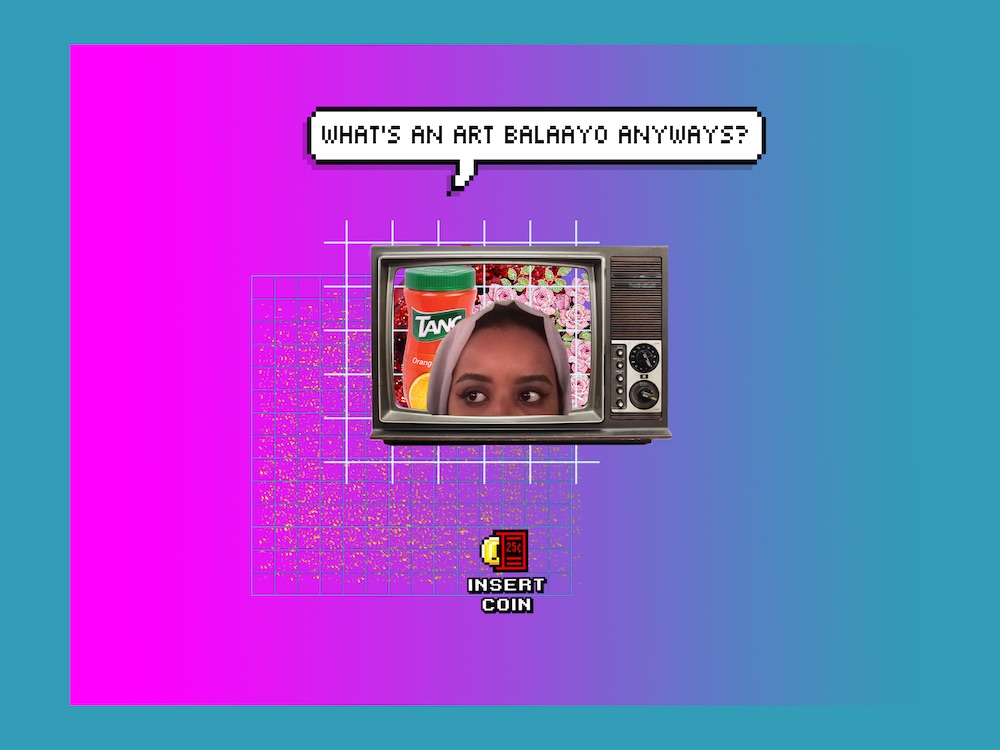

LA: Can you talk a bit about the Art Balaayo exhibit that just went down in London and the significance of that show? HS: The Art Balaayo exhibition was held at Red Door Studios, London, UK from May 5th to May 14th. Balaayo means trouble or bullshit in Somali. Over a year ago I co-founded a podcast with the name Art Balaayo, the podcast is currently on hiatus. Zeinab Saleh, the curator of the exhibition, was inspired by the name and wanted to make a space for young Somali female artists. For young Somali artists connecting is usually on the internet, we create our own communities so having that in the IRL is magical.

As Najma Sharif puts it “For those of us who grew up online, in countries outside of Somalia, the internet is as much a part of our culture as our ethnic identity” I couldn’t attend the exhibition but I felt like I was there via the URL. All of the women who were part of the Art Balaayo exhbition are amazing.

LA: I know you also do your own illustration, zines, and mini comics. Anything in particular you are working on at the moment that you’d like to share with us? HS: I’m currently working on a project featuring a character that floats around a lot-she’s ethereal and not fully human. Hopefully I’ll finish it by the end of summer.

Many of Halima's zines, such as Body Body: A conversation between the body and the self, can be read online. You can also keep up with Halima's work by following her on twitter@gothlime, following her on instagram (also @gothlime) and by visiting her tumblr.

© Copyright 2026, Maamoul Press