Iasmin Omar Ata tackles health through comics

Originally published October 13, 2016 on Bigmouth Comix.

Iasmin Omar Ata is a Palestinian-American artist and illustrator based in New York City. Their work spans from comics to game design, addressing issues as diverse as chronic illness, mental health, gender, and sexuality while incorporating elements of Middle Eastern culture and history into the storytelling. The result is work that is unapologetic about its complexities, that embraces non-normative, multi-faceted characters and insists on creating stories about them. I had the opportunity to interview Iasmin for BIGMOUTH to get more insight into their work, particularly their graphic novel, Mis(h)adra.

BM: Talk about your origins as an artist. How and when did you start drawing comics?

BM: Talk about your origins as an artist. How and when did you start drawing comics?

IOA: This is always the hardest question! I always drew a lot when I was a kid/teen (I got hooked on Sailor Moon when I was 8 years old), but all throughout that time I was discouraged by many people (not including my father, who has always wonderfully encouraged me to follow my dreams) from pursuing it as a life path, from creating non-normative characters/stories, and the like. I kept pushing forward, but it wasn’t until I moved to New York five years ago for school that I felt a rush of energy and a feeling that maybe this could actually work out! Ever since I got off that plane, I worked day and night to improve, and to fight the notion that I should erase myself and my characters. During my last year of school, I began to draw Mis(h)adra, and once that project formed, I felt like I had found my calling – like I was really creating work that I wanted to make and wanted to be seen. Now I literally can’t stop drawing. I’m trying to work on 500 things at once lol and sometimes it gets really stressful but I honestly, 1000% love it.

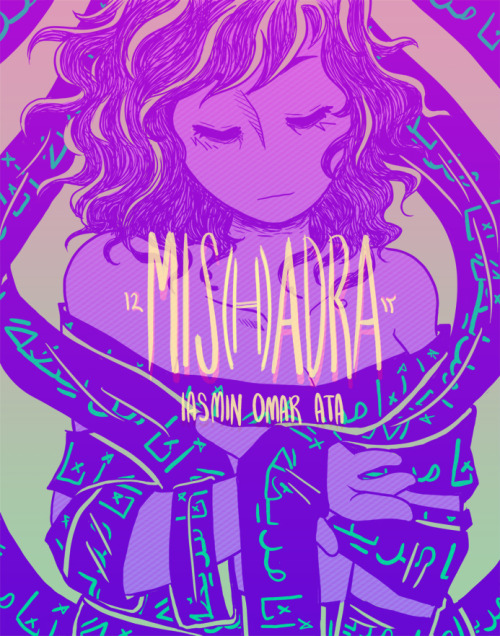

BM: There’s so much to discuss with Mis(h)adra, from mental health and chronic illness, to Arab identity and gender/sexuality. But let’s start with the title: How did you pick it and how does it tie together the themes of the story?

IOA: “Mish adra,” in my dialect of Arabic, means “I can’t,” or “I cannot,” and it’s layered with the word for “seizure,” misadra (sometimes transliterated as musadra/musadara), which is a play on the English word as well. So it’s kind of a cross-lingual non-literal triple pun lol. The (h) in parenthesis indicates that you can pronounce it either way, but usually people pronounce it with the h. The title ties into the literal meaning of “seizure,” but also the implications – feeling trapped, captured – the inability to act or to do something for yourself.

BM: The main character in Mis(h)adra, Isaac, is semi-autobiographical. What choices did you make in terms of how to portray him?

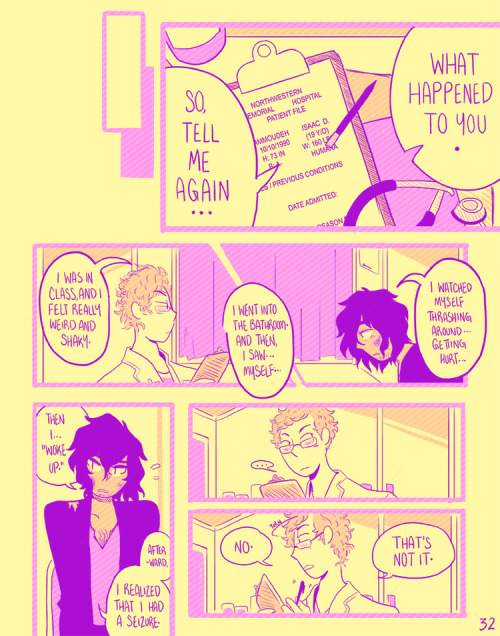

IOA: As a character, I wanted Isaac to represent myself and a time in my life where I was very confused about my illness and was on the border of just giving up for good. Isaac isn’t a Sadboy – we have more than enough Sadboy characters in comics! – but he’s just tired. He’s tired and doesn’t see much of a future beyond his incurable illness. The weight of dealing with such a dangerous condition that’s so stigmatized and misunderstood by society can be crushing, to say the least. He has a burden on his shoulders that he has no hope of lifting, so slowly he starts to get worn down – he gives up trying to talk to people, he gives up his meds, and near the end he’s on the brink of giving up his life. These are all very, very real things that I’ve dealt with in the past, and I wanted to bring them across as naturally as possible, so I just straight-up put in word-for-word dialogue and situations that I’ve been in during the span of my illness. I made a deliberate choice to have him experience all of it – not just the seizures, but the doctor’s visits, the late-night-outs, the classes, the day-to-day conversations with friends – because all of those things affect and are affected by my (and, in turn, his) epilepsy. I wanted him to be me, but I also wanted him to be himself, and to be real. And it turns out that readers instantly clicked with him – which was super cool!

It’s also worth mentioning that, when I was formulating the beginnings of Mis(h)adra, I was in a place in my life where I was quietly working through a lot of Gender Feelings. In the process of trying to figure this comic out, I decided to try inserting my experiences into a character who was of an identity that I had always kind of wanted to be, but was different from what I was assigned at birth. Basically, that choice started as an attempt to work out said feelings and thoughts through art, but it ended up setting a precedent that I could explore everything from an arm’s length away, and that guided both Isaac’s role in the comic and my own identity in real life.

BM: On a related note, how do you navigate the line between fact and fiction in your work?

IOA: The way I was brought up is like… for both cultural and personal reasons, I was strongly discouraged from talking about myself. That presented a problem for me when it came to making art. I tried for a while to do straight-up autobiographical stuff, but it just never worked! It always came out sounding unnatural and hollow – which makes sense, because it was totally forced. I struggled for a while trying to figure this out, because I really felt like I had a lot to say but just didn’t feel comfortable with autobio.

I started to find that voice when I decided to develop Isaac as a male character for my own personal unpacking. Not only did that make me feel more comfortable putting such sensitive information out there, but it also helped me come to my identity as agender – and it allowed me to examine and understand and refract these experiences from a different, but still very very close, perspective, which helped me work out a lot of issues I had with my illness. Mis(h)adra was basically a very intense 2-year-long therapy session! And as Isaac grew into his own identity, I felt myself growing along with him. So I guess the short answer is… I don’t navigate that line! The fact and fiction are so close in my work that it becomes hard to tell where that line is.

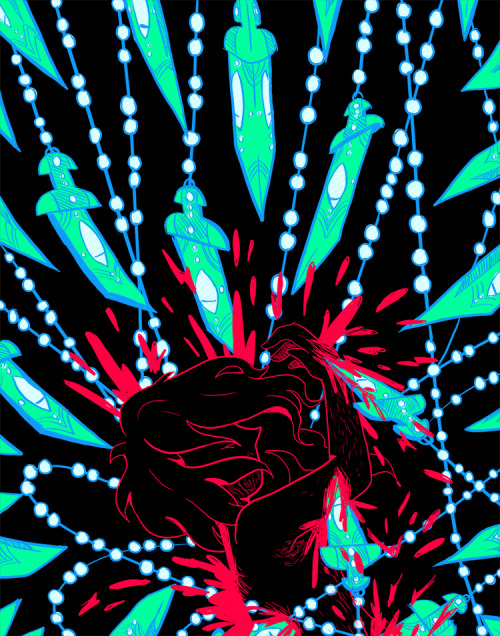

BM: You use distinct color schemes and surreal imagery to guide the reader through the layers of Isaac’s reality in the story, taking them in and out of dream sequences and epileptic seizures visually. Can you talk a bit about your imagery (particularly the images of knives being tied to epilepsy) and how you came to those artistic choices?

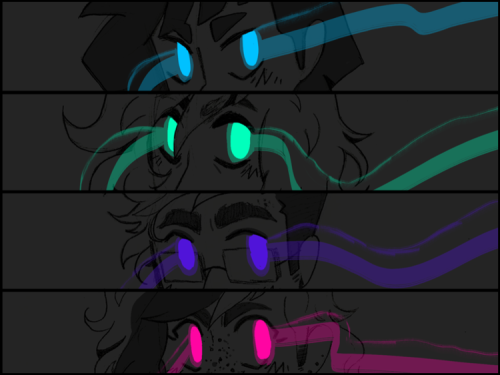

IOA: Coming up with the look and vibe for this comic was pretty challenging up front, because in reality not many people know what a seizure is like. I wasn’t sure how to find the words to explain the fear and the danger and the anxiety. But I learned that visual language can convey things when words fall short. During the mindspace both pre- and mid-seizure, the bright colors are supposed to evoke that danger and urgency, while the blank background implies that everything else around you fades away. On the flipside, the day-to-day palette is purposefully a little washed-out – bringing across the tired, drained feeling that Isaac experiences on the daily – and the purple linework is tied to Purple Day, aka Epilepsy Day, as well as the gem tourmaline which for a long time has been considered an aid to ward off seizures.

As far as the knives go: they are based on janbiya which is a specific style of traditional knife that’s iconic to the MESA/MENA world, dating back to the Ottoman Empire. It’s very tied to classic culture in these areas – it’s a weapon, and a very dangerous one at that, and it relates to the comic in the way that, to me, both seizures and the threat of seizures feel like having a knife to your throat, in danger of being sliced up or dissected. But on the flipside, in the right context, a janbiya can be worn for protection and personal strength. The eyes on the daggers are meant to represent the pressure, the idea that you’re always being watched by both people and the illness itself. Always on guard, never comfortable, always being watched, waiting for you to let your guard down so you get triggered into a seizure. The chains around the knives are the metaphor for the feeling of being captured, trapped, seized – playing into the title.

The overall goal for all this imagery is to illustrate something in a way that can come across to everyone – both epileptics and non-epileptic alike – something non-literal to open itself to a wider sphere of understanding.

BM: You also create games! How do all of your artistic and thematic interests impact your approach to game design?

IOA: Right now a lot of the game work I’m doing is art for two different projects – in one, I’m the character designer/artist, and on the other, I’m the background artist. So it’s cool because I get a lot of practice on both of those elements that are important to comics – in the cross-section of these two mediums, both of them inform the other. That’s part of why I love doing both comics and games – it’s such a unique combo!

The game I’m character artist-ing on – Four Horsemen – is actually about four teens coping with institutionalized racism and xenophobia.

Ultimately, I’m interested in games that don’t have easy choices, or games that make a player think / learn in ways that they haven’t before. I’ve been through a lot of complicated experiences – as you might guess from Mis(h)adra – so I like games that put you through non-normative eyes and difficult choices. Those are the kind of games that I like to work on and create!

BM: I know you also help with a lot of curatorial work at Babycastles in NYC. You’ve assisted with shows centering the work of Muslim artists (Salaamalaikum Babycastles), Arab artists (Habibicastles), and an upcoming show will center Palestinian artists (Art Palestine). What is the importance of doing this kind of curatorial work to you?

IOA: The importance of this stuff is really just – we exist and deserve to be seen! Arab artists – as well as MESA/MENA and Muslim artists as a whole – are constantly being passed up or treated as non-existent… or being treated with open hostility, even. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that it’s a fight to openly assert this identity and be listened to. Whatever I can do to help myself and others in this way, to help contribute to a solution for us – that’s what I want to do. It’s important for me to represent myself in my own work, but I think there’s a lot of good to be found in helping each other as a cultural-creative community.

You can view more of Iasmin’s work, including Mis(h)adra n its entirety, on theirwebsite. You can also follow Iasmin on tumblr, twitter, or Instagram @deltahead_ for updates.

© Copyright 2025, Maamoul Press