Love Letters to Iran: An Interview with Beeta Baghoolizadeh

Originally pubished February 16, 2018 on Bigmouth Comix.

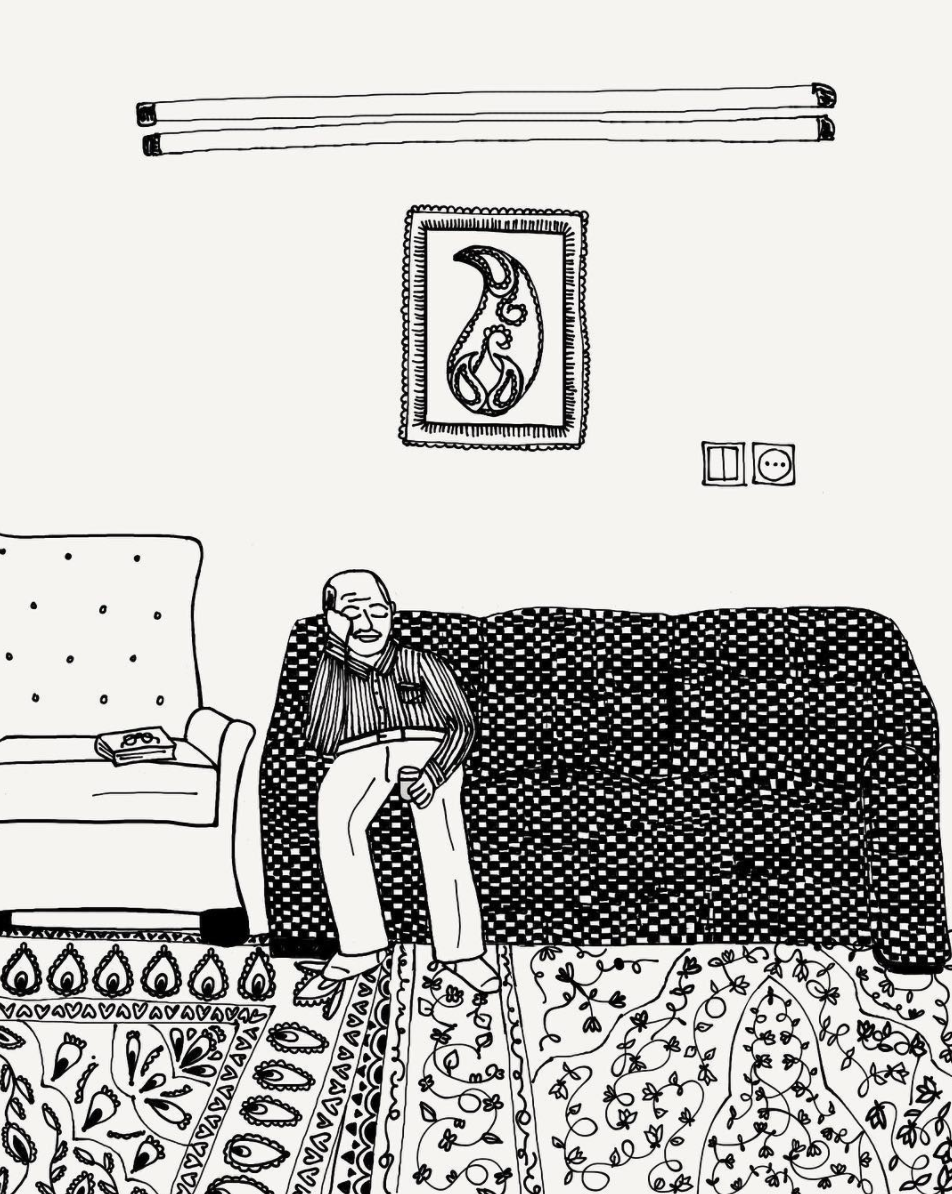

Beeta Baghoolizadeh is an Iranian illustrator, historian, and editor based out of Philadelphia. Her project, Diaspora Letters, is a visual tribute to a rapidly changing Iran. Using black and white illustrations and animations that are with texture and detail, the project is a historian-artist’s attempt to capture fragments of her homeland in the current time and place. Using drawings of primary sources like letters and photographs, as well as illustrations from daily home life and mundane family scenes, Baghoolizadeh’s work captures a piece of Iran’s ever-changing present, while acknowledging the persistent influence of the past. That the entire project, slated to become both a film and a graphic novel, is drawn within the context of diaspora, adds to the way that past and present run concurrently in her work, creating almost an archive of particular places, feelings, and people that cannot be captured through photographs or other primary sources alone. We interviewed Baghoolizadeh to find out more about her approach to her work, and how her multiple disciplines converge and influence each other in Diaspora Letters.

Leila Abdelrazaq: When did you begin creating art and illustrating? What drew you to this medium as a form of expression?

Beeta Baghoolizadeh: Well, I'm a historian of modern Iran, so I've traveled to Iran pretty regularly in the past few years to conduct research and visit my relatives. And this last time I was in Iran—August 2017—I was overwhelmed by how quickly everything in Iran changes. I had to reorient myself with new geographies and landscapes—streets, neighborhoods, etc. The rapid growth of the urban sprawl is a lot to take in.

So I started drawing. I started with my grandparents—I drew them, their house, just mundane scenes of the everyday. I felt that if everything is in a constant state of flux, I would need personal markers for preserving my memories, because it wouldn't be the same the next visit. But my drawings have developed in different directions, some more autobiographical, some more distinctly rooted in a broader history beyond my own family.

As a historian, I'm interested in how the past gets translated into the present. And visual media gets read and understood in such a different way than anything textual—so my arrival at this medium has helped me move beyond the limits of historical discourse.

LA: Tell us about how your drawings have developed since then. Where are you taking these drawings?

BB: In August, I started posting some of my illustrations on Instagram, where I've been able to share small anecdotes and relevant histories for the different illustrations. Most of these drawings will somehow be incorporated in one of two projects I'm working on concurrently.

The first project is a documentary film that I'm putting together with animator/filmmaker, Shane Nassiri. As it stands, the documentary will string together stories of families living in Iran and in diaspora in the 20th century, and how they remained connected through post. Mail—as you probably guessed from the name "Diaspora Letters"—has been an important theme for me. What kinds of things were being sent back and forth? Why? And what do they tell us about the political, social, and cultural environment? Those are the kinds of questions that we want to get at in this project.

The second project is a graphic history. I'm excited to be working on this book, which follows a family story and unravels some common preconceptions about urban family life in the past century. Iranians witnessed a lot of changes in daily life during the twentieth century, and I love the idea of exploring that visually, since words can only express so much.

LA: You’re also a historian and an editor at Ajam Media Collective. How are these practices linked for you, and how do they impact your approach to your creative work?

BB: Diaspora Letters grew organically out of my work as a historian and an Ajam editor. Part of being an editor at Ajam is making sure that people who are not necessarily academics have access to all sorts of amazing research on the Persianate world. A few years ago, I set up the Ajam Archive—a crowd-sourced digital archive of twentieth-century life in the Persianate world. It has been really exciting developing it, seeing what people are comfortable with sharing and what kinds of stories are behind the photographs, newspaper clippings, and clothes. Not only am I learning about the histories behind particular items, but I'm also learning about what people feel they can and can't share from their family collections.

Those sorts of absences are, for historians, really interesting. And that's what I think this illustrative medium offers in terms of histories—it can show what didn't get photographed, or what people didn't want to photograph, or what people photographed and don't want to show on a public platform. There's a lot missing in these conversations, and drawing them fills the gap to some extent. Of course, the drawings themselves just as selective as the photographs—I can’t show everything that’s missing! But theoretically, the drawings can show anything, and that excites me.

All of these experiences inform my graphic work. I want people to access and navigate their own relationship, visually, with the material. It evokes a different series of emotions than an article, and I wanted to be able to tap into that.

LA: You often work from photographs, letters, and other artifacts. How do you select these objects and what is the importance of integrating them into your illustrations?

BB: I love working with tangible objects and abstracting them in my drawings - this practice is definitely influenced by my academic training. In some ways, I'm trying to stretch how far textual analysis of primary sources can get us - instead of realistically replicating the written word in my work, for example, I deconstruct them into scribbles, forcing the viewer to rely on the entirety of the illustration to determine the context. It's very different than how we use sources in history, and I appreciate the flexibility illustration affords me in pushing these boundaries.

I work from photographs, but a lot of the illustrations don't necessarily end up looking like the people in the original photographs. In some ways, I'm trying to anonymize and vernacularize the images. So I'll change the shape of the eyes, nose, lips, etc - an urge very different from the kind of typical academic work that requires attention to accuracy and faithfulness to the sources we use.

Sometimes it works, and the result is different people telling me that the person looks like their aunt or some other relative. Other times, my mom will look at a drawing and say, "Wait, that's me! That's my hair!" I love both types of reactions and make note of them as they happen.

Outside of the Diaspora Letters exhibition at 12Gates Arts in Philadelphia, PA. Photograph by Sahar Irshad.

Baghoolizadeh with some of her illustrations and animations, on display at 12Gates Arts in Philadelphia, PA. Photo by Sahar Irshad.

LA: Since you’re creating these illustrations in the context of a book and film, how was the process of using those images to put together your solo exhibit at 12Gates Arts? Did it change the way you’re thinking about the process of creating the book?

BB: Working with 12Gates and sharing my digital drawings as individual, stand-alone pieces has been a very generative process for me. The 12Gates exhibit mostly focused on scenes of everyday life - the banal, the mundane, the sort of things that are too boring to be circulated in the media or preserved in institutional archives. Even though a lot of the pieces I showed at 12Gates fit into a larger narrative arc, showing them in no particular order with no linearity allowed me to explore the theme of fragmentation. Everything we can know about Iran is ultimately fragmented, not only because of the diasporic distance, but also because of how quickly everything is changing. It’s good to remember this that when writing stories—real life changes in unexpected ways, leaving behind the past more rapidly than we sometimes expect.

LA: You often reference your family’s reactions to your drawings in your instagram posts. It seems the process of creating this work is one that involves your entire family in a very intimate way. What do you think is the significance of creating work in this way?

BB: I love my family and I love incorporating them into my work as both subjects and consumers. They have a great sense of humor, and when I can refer back to a quip from my grandpa or someone else, it lightens the heavy emotional content underlying the process.

In many ways, my drawings are all kind of love letters to not only to Iran, but also to my family all over the world, the majority of whom still live in the homeland. Even though I'm fluent in Persian, there are conceptual barriers that language can't overcome, so the visuals help.

You can follow Beeta's work at @diasporaletters on Instagram and Twitter, or follow her personal Twitter account @beetasays. And if you would like to be in touch with Beeta, shoot her an email at beeta@diasporaletters.com.

© Copyright 2025, Maamoul Press