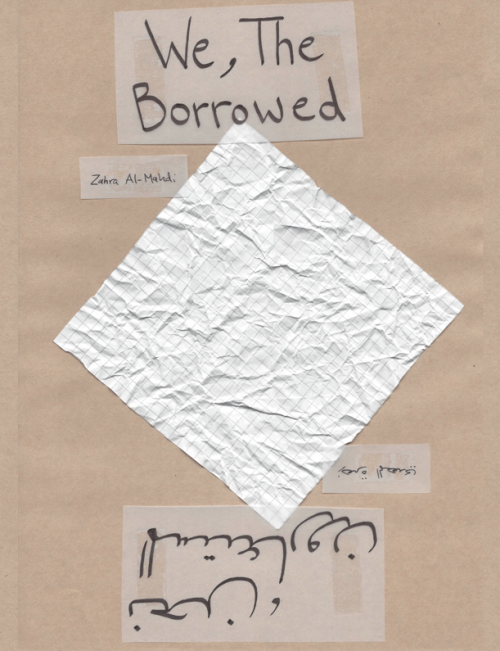

Zahra al Mahdi's We, The Borrowed

Originally published September 5, 2016 on Bigmouth Comix.

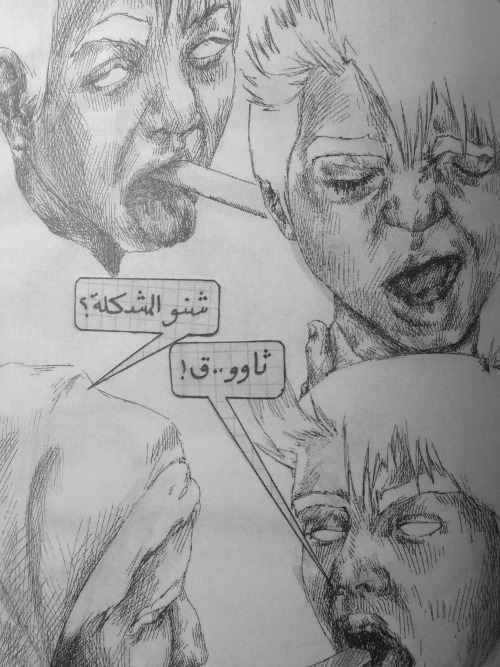

Zahra al Mahdi is a comics artist from Kuwait. She is the author and illustrator of the bilingual, absurdist, and politically charged graphic novel We, The Borrowed/نحن، المستعارون.

I interviewed Zahra to ask her about her graphic novel, which was originally self published, but has recently been picked up by Kuwaiti publishing house Dar Al Farasha.

BIGMOUTH: How and when did you get into drawing comics? What drew you to this particular medium?

ZAHRA AL MAHDI: I’ve always been interested in stories and illustrated books since I was a child. I was first exposed to the medium of comic books (officially) through translated DC comic books. Superman was my favorite. I found that I’d grown out of it by the time I stumbled onto Alan Moore, Harvey Peekar, and Marjane Satrapi. My first comic sheets were autobiographical, more or less in the traditional sense, and very reflective of the style that I’ve been exposed to. By the time I graduated from University, I felt the need to add to the medium by using it differently. I wanted to change the form and really apply everything I’ve learned from literary and cultural critical theory.

BM: What was the inspiration behind your graphic novel We, The Borrowed? When did you start working on it and what was that process like?

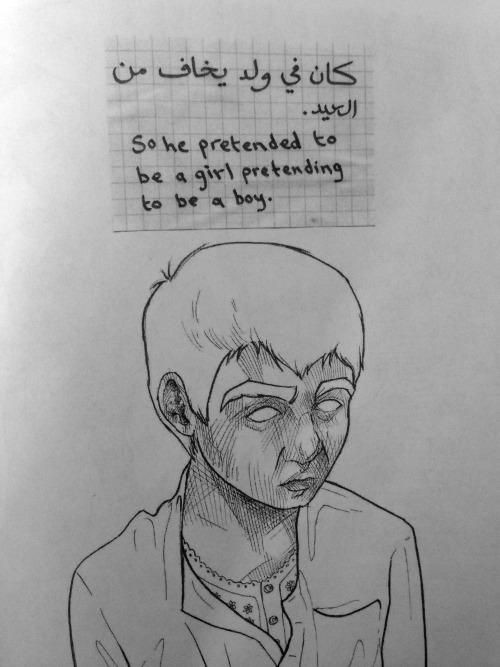

ZM: My obsession with the ludicrous patterns that bureaucracy, and bureaucratic systems, are based on, are very prominent in the book. People often create overly complex systems with the intention of making certain procedures easier, while ironically crippling it severely. Being influenced by Kafka, Foucault, Sartre, and Butler, among other thinkers, I wanted to express how I saw these systems in a way that might prove productive. And if not productive, at least whimsical. I often say that I am bureaucratically-challenged, as I seem to find difficult what other people think is perfectly self-evident, or axiomatic. “We, The Borrowed” was intended to be my last self-portrait. I spent three and a half years writing and illustrating it right after graduating, and throughout graduate school years.

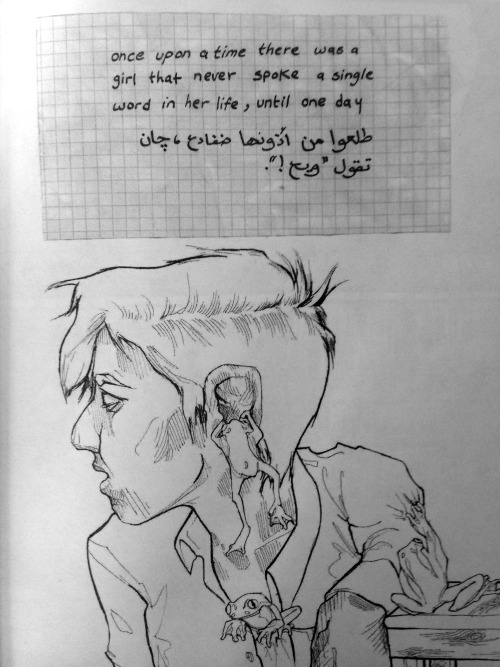

BM: You use surreal imagery alongside cryptic language in your work. Your stories seem to take place in an alternate universe where time is non-linear and the strange is normal. Why are unconventional storytelling techniques important in the context of your work?

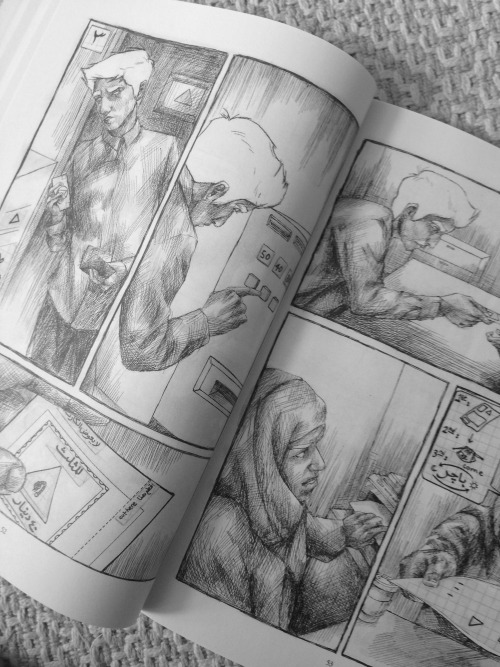

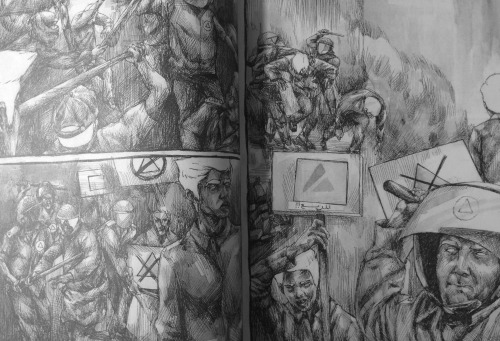

ZM: Sicence Fiction is my favorite form (not genre) of storytelling. I dislike the association of sci-fi with the necessity of a futuristic or highly technologically-developed setting. Sci-Fi narrative is usually set in an alternate world that criticizes issues in the one we are in. In the story, I turned black magic or voodoo into a government regulated system…My intention was to normalize surreal and ludicrous elements and events in order to point out the absurdity of our reality.

More importantly, I wanted to comment on the way graphic novels have been adapted into films. Or rather people’s understanding of the adaptation of graphic fiction. The majority seems to think that comic books are storyboards for films, and therefore their adaptations should never veer off of the literal events. I felt that I had to create a work that could only be told visually, complimented by necessary glyphic elements. Thereby, if this book were to ever be adapted, it would have to be completely rewritten to fit and truly adapt into a different medium.

BM: Your work makes minimal use of language, and your book is actually bilingual, fusing Arabic and English sentences and phrases together. Despite this minimal usage, it’s clear from the jokes in the book and sharp use of language that wordplay is very important to you. Additionally, the issue of language is a central theme in the second half of the story. Can you talk a bit about your own relationship with language and how it impacts your work?

ZM: I am severely bilingual, and I speak both languages interchangeably with my family and friends. I often find it difficult to tell a complete story without slipping a few words or phrases from the other tongue. And since writers usually use the language they speak with, I had to use a combination of both. Also, the Kuwaiti dialect often fuses english words with Arabic prefixes and suffixes, which made it easier for me to write bilingually.

Despite the fact that I’ve learned to read and write in both Arabic and English simultaneously at a relatively young age, I still found it difficult to express myself linguistically. Because of that I had to find a way to create a more visual language; one that isn’t very cryptic, but is still fluid enough to carry layers of interpretation. And because I am a believer of all that Foucault has to say about language, and how it’s usage has direct impacts on our physical bodies, I thought it would be interesting to not mention the words themselves that shape us, but rather the symbols and connections that they imply. And since language (especially in my culture) is an amalgam of different cultures that we falsely claim to be “originally” and “authentically” Kuwaiti, then it is a language that we have only borrowed. And perhaps that could say a lot about who we are “originally”.

BM: We, The Borrowed also seems to be a response to political situation in Kuwait. Can you talk a bit about the intersection of art and politics in your work?

ZM: The region we live in exposes us to a lot of political conflicts, yet we remain sheltered and lulled into the illusion of complete stability. After the Arab spring, Kuwait tried to get on board with the chain of revolutions, and to me that revealed a lot about the nature of the Kuwaiti people. I find that there is an immense drive for change but little to no knowledge of how that change should occur, and to what end it should be. So I thought that, more or less, an allegory about the dangers that an uninformed and misguided revolution could result in.

BM: Who are some of your inspirations in terms of art and comics?

ZM: I’ve mentioned Satrapi, Moore, and Pekar. I am influenced by, and continue to relate to the work of Charles Burns. The best Science-fiction writer in my opinion is Ursula K. Le Guin. I’m also majorly inspired by filmmakers such as Michel Gondry, Lars Von Trier, Yorgos Lanthimos, Oliver Assayas, Wes Anderson, the Coen Brothers, and the Nolan brothers.

BM: Anything else you would like to add that I didn’t ask about?

ZM: It was at first difficult to find a local publisher because of the form I chose for the book. Naturally, publishing houses thought it was too risky to publish a book of what seemed to be visual gibberish. I had to self publish to prove that it would actually sell. Dar Al Farasha here in Kuwait picket it up and the (much much better) print came out early August. It’s sold only in Kuwait, and any of the regional book fairs the publishing house participates in.

At the time of publishing this interview, two copies of the first, self-published edition of We, The Borrowed are still available on Amazon, so if you live outside of Kuwait and want a copy, snag one here before they are all gone!

More of Zahra’s short comics have been published on Jaffat El Aqlam, and you can follow her on instagram @zouzthebird for new work.

© Copyright 2025, Maamoul Press